The Year 2025 Will Not Take Place

Text

This exhibition reintroduces Mutlu Çerkez’s practice to a new audience, almost twenty years after his passing, through a two-act structure. At its core lies a commitment to a methodology that resists the conventions of progress: questioning originality, the hierarchies and distinctions between genres, and the assumption that we operate within an artistic system that privileges evolution and resolution over time. For Çerkez, artworks exist in a temporal contradiction—at once already in the past and deferred into a future. His was a practice, and this is a show, staged in permanent rehearsal.

Act I

Act I–taking place on November 12, 2025–restages a performative gesture first presented in Mutlu Çerkez: selected works from an unwritten opera at the Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, in 2000. In that exhibition, Çerkez reworked material from the Notes and More notes for an unwritten opera series (1997–1999), transforming an earlier work—a mute Marshall stack, Untitled: 14 July 2030 (from Stage furniture / props for an unwritten opera, 1999), switched on but unplugged—into a live sculpture incorporating a Moog theremin, the same model used by Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page in Whole Lotta Love. It was a rare moment where Çerkez involved visitors, inviting them to contribute to his work by playing the instrument. Their improvised sounds were recorded and later released as a CD accompanying the exhibition catalogue. Following Çerkez’s conceptually underpinned score, the same gesture was repeated at the gallery in Athens in 2025–visitors activated the theremin again, their performances recorded and released on the gallery’s website. The act was both an homage and contribution to Çerkez’s practice, and a prelude to the exhibition that follows.

The work draws on two continuous currents in Çerkez’s practice. The first is the ongoing series An unwritten opera, initiated in 1992, which evolved through successive bodies of work—Notes, More notes, Make-up design studies, and Studies for the score—each expanding the conceptual idea of the original. Adopting the opera as a structural device rather than a narrative form, Çerkez used it to fold painting, set and graphic design, musical composition, video, and poster studies into an ever-expanding system of fragments that, together, might conceivably constitute the “opera.” Yet the semantics of their titles—the temporal contradiction between “unwritten” and “notes,” “studies,” “scores,” and “designs”—reveal these works as potential conspirators only to an unwritten narrative. Throughout these bodies of work, the “opera” functions as an open framework, positioned to absorb whatever is designated as part of it precisely because it remains in a continual state of incompletion. Çerkez imagined the production always proceeding “as though being watched in rehearsal”–a stage for unfinished material, now also without its author. Each work, then, extends the project without resolving it, continually deferring the possibility of its legibility.

A second current in Çerkez’s practice runs parallel: his enduring engagement with Led Zeppelin. A dedicated teenage fan, he often recalled how he had once stopped listening to their records because he “knew every smallest sound off by heart,” even the “squeak of the bass drum pedal.” Years later, a bootleg recording of a live concert renewed his fascination—“it was all different again”—and permanently folded the band’s presence into his practice. The bootleg, never identical despite returning to the same source, chimed with Çerkez’s own logics of production. Both imperfect and illicit, it became a model for an artwork that resists closure: not meant to endure, yet captured, replayed, repackaged, and recirculated—complicating notions of value and originality, and locating the potential for creativity precisely within repetition.

Act II

Act II–opening on November 22, 2025–unfolds as an exhibition of works by Mutlu Çerkez—installation, painting, video—accompanied by a conceptual continuation of his practice and a performative lecture on his work by Jeff Wall Production.

Alongside the opera’s open structure and the bootleg’s iterative logic, two further moments sharpen the understanding of this life-as-work—each reinforcing Michael Graf’s concise rejoinder to accusations of arbitrariness: that Çerkez’s project is, fundamentally, “work that anticipates the works he will make at a future date.”

One moment that proved foundational occurred during Çerkez’s student years, convinced he was looking at a Giorgio de Chirico metaphysical work from around 1915, only to realise—almost in disbelief—that it was dated 1975. De Chirico had achieved early acclaim for those metaphysical paintings, only to spend the next six decades sidelined after turning toward a classicising style the avant-garde rejected. As collectors and the public continued to covet the early works and overlook the rest, de Chirico began remaking them—producing copies and “later versions,” notorious as acts of self-forgery. The anecdotes multiplied: dealers joked that his bed sat six feet high to make room for the “early works” he kept “finding” beneath it. This deliberate looping of time—at once capitulating to and sabotaging audience expectations—became a key parable for Çerkez. It also crystallised a broader dilemma: within the mechanisms of the art world, newer work is expected to supersede what came before, rendering earlier efforts valuable only as steps toward a supposedly more mature, more definitive future practice. Çerkez found this logic difficult to accept, and various forms of resistance to it would come to shape the parameters of his own practice.

Following from this, perhaps the most radical parameter in Çerkez’s practice was his decision, in the early 1990s, to begin forward-dating his works, embedding a conceptual and temporal proposition directly into their titles. In this structure, works had the date of their original execution paired with an imagined future earmarked for its eventual remake, projected across the full span of his life expectancy, along with the number of days he would have been alive on that date. To illustrate: Untitled 22095 (15 March 2025), 1992—a self-portrait of Çerkez swimming underwater, drawn from a photograph taken during his return to Cyprus, both in 1992—was conceived not only as a work from that year, but as one meant to be re-created on 15 March 2025, the day he would have been alive for 22095 days. Lifespan, postponement, and recurrence were folded into the architecture of the work itself, so that each work stands as both finished—titled, exhibited, allowed to circulate—and fundamentally incomplete, dependent on a future date to finish its circuit. This temporal doubling pressurises the present, positioning it as the point of contact between an affirmed past gesture and the future the work insists upon.

Jeff Wall Production’s contribution to the exhibition enters this logic directly, treating the forward-dated works as calls addressed to others—requests to resume what Çerkez projected into the future but could no longer carry out after his death in 2005. The works on view extend this proposition: reproductions from Çerkez’s monographic catalogue—cut from their pages and framed—will be hung on the exact dates they were meant to be re-enacted, allowing the present to meet the future they set in motion. The performative lecture that opens Act II follows the same trajectory, returning to a key future-dated work—Freeway sound barrier: 12 August 2027 reference – Untitled 22101 (21 March 2025), 1992; Untitled 22107 (27 March 2025), 1992 from More notes for an unwritten opera, 1997—first proposed by Çerkez for documenta11 under Okwui Enwezor; here acknowledging Pierre Bal-Blanc’s (who stands behind the aegis of Jeff Wall Production) own involvement as a curator during documenta14 under Adam Szymczyk (part of which, crucially, unfolded here in Athens); and now projecting the work forward toward documenta16, scheduled to open next year under Naomi Beckwith—fittingly, taking into account Çerkez’s forward date, 2027.

Like the Marshall stack–now turned on but unplugged, itself also a contradictory setting–which was centered in Act I, the curtain bearing the phrase “design for the overture curtain of an unwritten opera” sits firmly within the ongoing series An unwritten opera. The curtain wears its contradictions on its sleeve: the moment we read it, the work discloses its recursive structure. The “design” is in fact the curtain, and the curtain is already performing its role as an overture, but there is no opera. The finished work is only a proposal, yet the proposal is already complete. We stand before something that is both about to begin and already underway—an opening that starts, and ends, the instant we encounter it.

Beyond its temporal play—its recursive structure paired with a forward date embedded in the work’s title—the curtain also underscores the importance of form in Çerkez’s practice. Perhaps paradoxically for an artist so deeply grounded in conceptual methodologies, works that could have been produced through the quick efficiencies of printmaking are instead realised through the slow, deliberate, and traditional mode of painting: each letter circled, dotted, and edged by hand, the negative space painted in rather than the letters themselves. This insistence complicates any easy divide between conceptual proposition and material form. The same logic extends to other works—such as the Poster design variations for artists’ publications—where Çerkez paid tribute to close friends and collaborators like Stephen Bram, Rose Nolan, and Marco Fusinato, as well as to Led Zeppelin, through typographic announcements of forthcoming publications or records, also painstakingly rendered by hand.

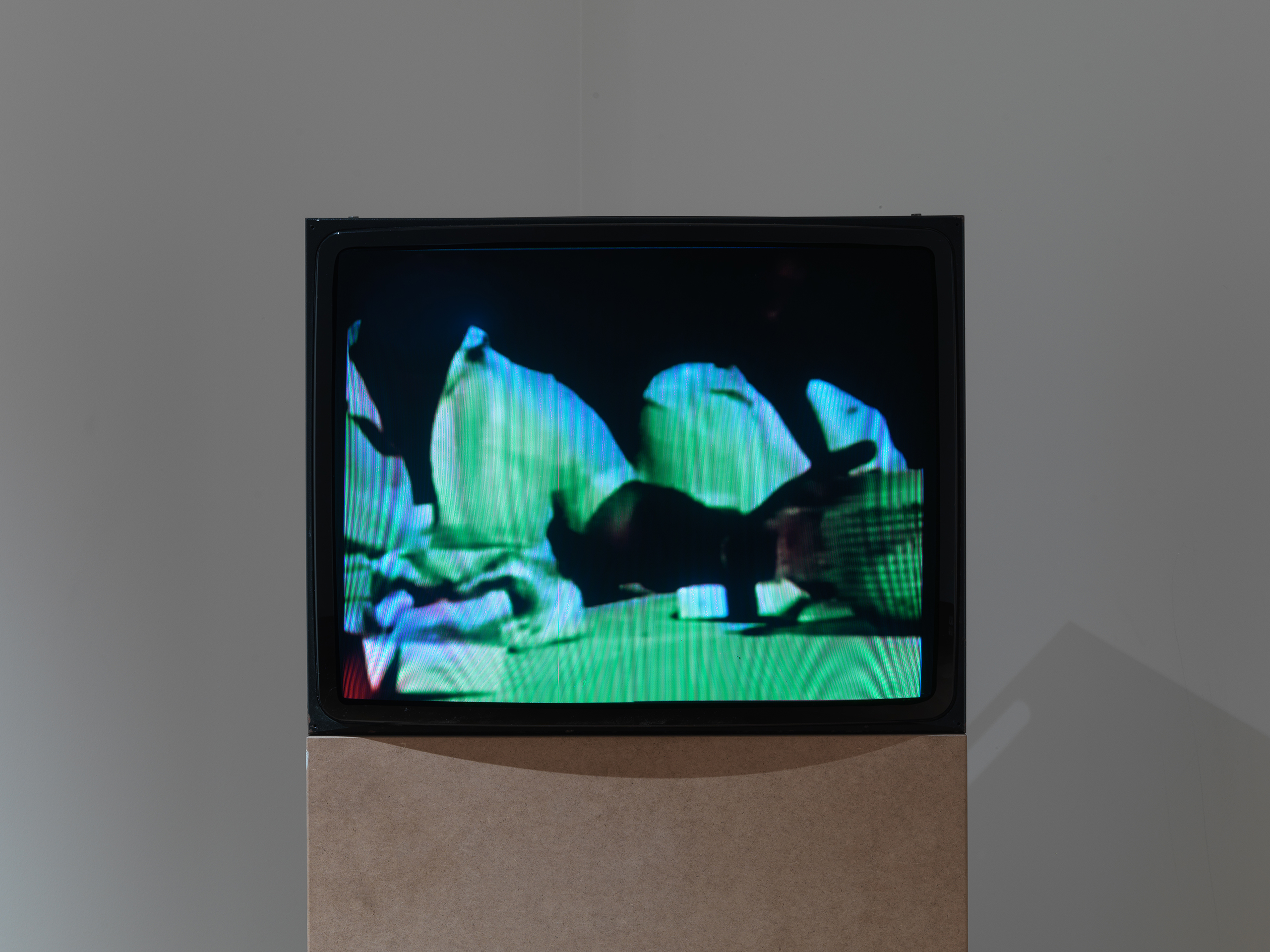

This last series introduces an essential counterbalance to what might otherwise read as a practice that—shaped by hermetic networks, self-reflective language, and a repertoire of lists or silenced amplifiers—could be misconstrued as cynical. This is where the video work, After dinner conversations in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, 1994, also becomes important. Emerging from a formative trip Çerkez made to his native Northern Cyprus in 1992, which generated both this film and a related group of paintings, it stands as a rare—though not singular—instance of his use of video. Shot during a family gathering, a camera placed on the table records a conversation in Turkish among a group of men whose heads are mostly cropped from the frame, the focus settling instead on the rakı sofrası (the raki table). The footage is brief and non-narrative: a document of indistinct exchanges, fragments of talk, and the social atmosphere of the moment: a mention of “Şeyh Nazım!” (the late Turkish Cypriot Sufi leader), reminders to finish the food, and a run of inside jokes.

Despite the scene’s hermetic surface, the work makes clear that heritage, local histories, personal relationships, and peer networks were not absent from Çerkez’s practice but foundational to it—woven through the work rather than eclipsed by its conceptual structures or his refusal of conventional self-expression and collaboration. What can appear opaque from the outside is, in fact, sustained by lived ties, by the geographies and relationships that shaped his life-as-work. Beyond the poster-design tributes to his peers and idols, other works from this homecoming trip make this apparent too: paintings imagining the future drowning of Cyprus and its speculative division into two islands (both the imagined result of a natural catastrophe and a proposed resolution to the ongoing conflict); a nocturnal mountain landscape bearing the Turkish flag; or an image of rubble on the building site of his homeall map the relational and geographic foundations of Çerkez’s practice as decisively as its structural propositions.

In closing, the exhibition’s title—borrowed from Rex Butler’s 1999 essay on Çerkez—offers both the context and the coordinates for our engagement with the work, and the path along which its iterations may continue. In that essay, Butler draws on Baudrillard’s claim that the year 2000 “will not take place”: not because it fails to arrive, but because it has already been lived in advance, a temporal marker exhausted by anticipation yet endlessly deferred, fully imagined and still strangely unforeseeable. The apocalypse, rehearsed so obsessively across the twentieth century, loses its force when it finally appears. We inhabit the present as though the ending has already occurred, as though we are living on after our own conclusion.

This exhibition moves within that same unsettled temporality: The Year 2025 Will Not Take Place. Several of Çerkez’s forward-dated works designate 2025 as the moment of their imagined remaking, binding the work to a future that is now our present—one saturated with continual forecasts of environmental collapse, geopolitical thresholds, astrological turns, technological ruptures. Time feels both tipped and perpetually imminent. This is, then, the centre of the chronology Çerkez’s practice inhabits: not anticipation or delay alone, nor a position outside them, but the interval where both collapse, a self-reflexive register in which the present is never quite stable. It may be this very instability that renders the work so contemporary—something that must be remarked precisely because it cannot be held. In this sense, Çerkez’s practice continually re-marks the impossibility of the present, allowing 2025 to become, again and again, the “now” of every moment.

Alongside the more nebulous forces of time, this exhibition was also shaped by very immediate forces: artistic license; collaboration and support; shared convictions; and the alignment of long-term alliances with our own, newer enthusiasms. In this spirit, our sincere thanks go to the generous group of artists, curators, and friends who made this exhibition possible: most importantly to Anna Schwartz, Charlotte Day, and Mat Çerkez, for their guidance, trust, and permission to bring this project into being; to Francis Upritchard, David Noonan, Marco Fusinato, Stephen Bram, and Misal Adnan Yıldız, whose close proximities to the work or its far-reaching networks helped us trace, gather, and understand the material that grounds the exhibition; to Nic Tammens for first bringing the practice into our view; to Pierre Bal-Blanc for deftly introducing it into our programme through Jeff Wall Production; to Aycan Garip and to Rahme Veziroglu for their vivid and detailed translations of the video; and to everyone at Monash and MUMA—Ruth Bain, Rebecca Coates, Emma Neale, Madeline Mondon—who unearthed, shared, and shipped what we needed on timelines that should have been impossible.

All citations of Michael Graf and Rex Butler, along with the broader scholarship that supports this exhibition, are drawn from Mutlu Çerkez: 1988–2065, the exhibition curated by Charlotte Day and Hannah Mathews and its monograph published by MUMA, both in 2018.

Bio

Mutlu Çerkez was a conceptual artist whose practice explored its own temporality and sought to create a conversation between past actions and future scenarios. Each new work was ascribed a future date on which he intended to remake the work.

Working in a range of mediums including printmaking, painting and sculptural installations, Çerkez employed abstract designs and aphoristic symbols to expound upon time and reality and build upon the conversation between past actions and future scenarios.

Born in London, in 1964, he and his Turkish Cypriot parents immigrated to Australia later that same year. The artist’s reputation quickly grew from support in Australia and New Zealand, to being internationally renowned. In 2005, Çerkez passed away in his Melbourne home.

Selected exhibitions include Mutlu Çerkez: 1988 – 2065, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne (2018); Self-consciousness: Contemporary Portraiture, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne (2012); Networks (cells and silos), Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne (2011); Mutlu Çerkez, Istanbul (2006); New05, ACCA, Melbourne, (2005); 2nd Auckland Triennal, Auckland (2004); Fieldwork Australian Art 1968 – 2002, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (2002); Selected Works from an Unwritten Opera, Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki (2000); Auditions for an Unwritten Opera, Artspace, Sydney (2000); 6th Istanbul Biennial, Turkey (1999); Sao Paolo Biennale, Brazil (1998); and Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney (1988).

Selected public collections include the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Kiasma, Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; and Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth.